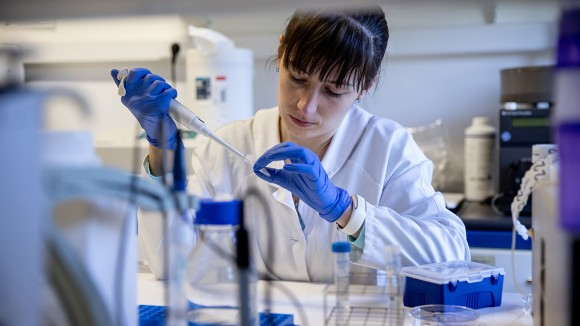

Long before discoveries were named or papers were published, there was curiosity.

Not the kind that announces itself as brilliance, but the quieter kind that lingers. The kind that returns to the same questions again and again without demanding quick answers. For this scientist, early curiosity didn’t look like genius. It looked like attention—sustained, patient, and often unnoticed.

Those early years didn’t feel exceptional. They felt absorbing.

Curiosity Began With Observation, Not Ambition

In the beginning, there was no intention to become a scientist.

There was simply a habit of noticing—patterns that repeated, inconsistencies that stood out, and details others passed over quickly. Curiosity didn’t come from wanting to achieve something specific.

It came from wanting to understand.

Questions arose naturally from observation, not from pressure to perform.

Questions Were Allowed to Stay Open

One defining feature of this early curiosity was tolerance for unanswered questions.

Not everything needed closure. Some questions lingered for months or years, revisited as understanding slowly changed. There was no rush to resolve uncertainty.

Uncertainty wasn’t uncomfortable.

It was familiar.

This comfort with the unknown later became foundational.

Exploration Happened Without Structure

Early exploration wasn’t formal or organized.

There were experiments without labels, reading without clear purpose, and tinkering that didn’t lead anywhere obvious. Learning followed interest rather than curriculum.

Progress wasn’t tracked.

Understanding accumulated quietly.

What mattered was engagement, not outcome.

Mistakes Felt Like Part of the Process

Early missteps didn’t feel discouraging.

Experiments failed. Assumptions proved incorrect. Attempts had to be rethought. These moments didn’t carry emotional weight—they were simply part of figuring things out.

Failure wasn’t interpreted.

It was absorbed.

This reduced fear and kept curiosity intact.

Curiosity Was Personal, Not Performative

The interest was inward-facing.

There was little concern with explaining ideas clearly or proving understanding to others. The motivation came from internal satisfaction, not recognition.

Curiosity didn’t need an audience.

It thrived in private engagement.

This inward focus allowed ideas to mature without pressure.

Patterns Became More Interesting Than Answers

Over time, attention shifted subtly.

Individual facts mattered less than patterns connecting them. Curiosity moved from isolated questions toward relationships—how one thing influenced another, how systems behaved under different conditions.

Understanding became layered.

Depth replaced accumulation.

This pattern-oriented thinking later shaped scientific approach.

Reading Followed Interest, Not Obligation

Books and resources were chosen intuitively.

Some were abandoned halfway through. Others were returned to repeatedly. Reading wasn’t about coverage—it was about resonance.

Interest guided attention.

Attention shaped memory.

Learning felt organic rather than imposed.

Time Passed Without Clear Direction

Years moved forward without a defined path.

There was no urgency to label the curiosity or turn it into a career. The absence of pressure allowed exploration to continue without narrowing too soon.

Direction emerged gradually.

It wasn’t chosen—it was noticed.

Curiosity Adapted as Understanding Grew

As knowledge increased, curiosity didn’t disappear.

It shifted. Questions became more precise. Exploration became more focused. But the underlying impulse remained the same—follow what doesn’t yet make sense.

Curiosity matured without hardening.

It stayed flexible.

This adaptability allowed continued growth.

Early Curiosity Built Endurance

Perhaps the most lasting effect was endurance.

The habit of staying with questions—even when progress was slow—built stamina. Long stretches without answers didn’t feel like failure.

They felt normal.

This endurance later supported sustained research and deep inquiry.

The Early Years Didn’t Feel Important

At the time, none of this felt formative.

It felt like interest, distraction, and exploration without consequence. Only later did these patterns reveal their influence.

Meaning arrived in hindsight.

The foundation had already been set.

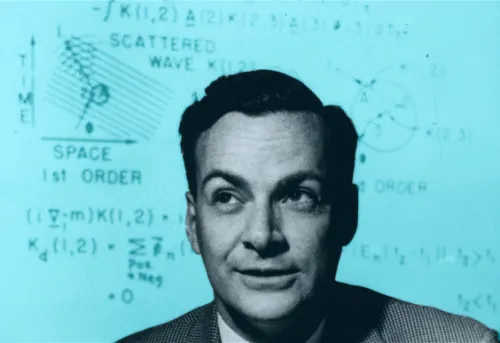

A Gentle Closing Reflection

The early curiosity that shaped this scientist wasn’t extraordinary.

It was quiet, persistent, and unhurried. It didn’t aim for outcomes or recognition. It simply stayed with questions long enough for understanding to deepen naturally.

Many people imagine scientific curiosity as sudden inspiration.

Often, it’s the slow habit of paying attention—kept alive over years—that shapes how discovery eventually happens.

AI Insight:

Many people notice that early curiosity often feels ordinary at the time, only revealing its lasting influence much later.